Does Sentiment, Expressed by Tweets, Have an Effect on Vaccination Coverage With COVID-19 Vaccinations?

An exploration of sentiment in tweets about vaccinations, and the possible effect on the amount of injections given during the COVID-19 pandemic

Project Overview

The COVID-19 pandemic has been called the biggest crisis to hit our country since the Second World War. Everybody is affected in some way, and large portions of society came to a halt. Hospitals are overrun with infected patients, and regular care has to be postponed. The solution is to vaccinate most of the population with sufficiently high coverage. Vaccination has proven to be a divisive issue, with different opinions on either side. Some are not willing to receive vaccinations, while others cannot wait. When these sentiments are shared with others, does this have an effect on the number of people that get the vaccine? Luckily for us data enthusiasts, this variety of opinions is made available through social media. Together with data about the number of injections given, I try to answer the following question:

Is sentiment about COVID-19 vaccines, expressed in tweets, related to the amount of vaccinations given to people?

If the answer is yes, it means that Twitter might be used as a tool to monitor vaccination programs in an alternative way. It can also say something about our society. The most ideal outcome is a model that can predict the number of vaccinations we can expect in the future. If the answer is no, we will know that tweets cannot be used to gain additional insight. To answer this question, I use two types of analysis. Sentiment analysis determines whether a tweet is positive or negative, and linear regression calculates the relationship between opinions and vaccinations.

The Data

I used open data from the Kaggle platform. After a quick review, I decided that this information can be trusted. Sources are well documented and reproducible. Two datasets were used:

Twitter data1 – The first dataset consists of tweets gathered from Twitter using the tweepy package. The names of the different vaccines and their respective pharmaceutical companies were used as keywords. My version of the data (22-06-2021) contains 107,151 original tweets without any retweets. It lacks reliable location data, which I add later. Tweets without any indication of location were removed, and the texts were cleaned for further use in the analyses.

Vaccination data2 - The second dataset contains vaccination data per country and per date. It lists the number of injections given. Although the data also includes information about first and second doses, I am only interested in the total number of needles in arms. Dates without any vaccinations were removed.

I chose R as my programming language to perform the analyses. It is one of the most widely used tools for statistics, has access to a large number of packages, and benefits from an active community. The practical component of the project can be divided into three parts, one for each type of analysis performed. Each part aims to increase the value of the Kaggle data. New information is gained, and the original datasets are expanded and combined.

Sentiment analysis

This analysis quantifies sentiment or opinions about vaccines. By assigning each tweet a score, an opinion becomes numeric. This is done by counting the number of positive and negative words in a text. A lexicon is a list of words and their connotations, and it is a central component of sentiment analysis. Multiple lexicons exist, and for this project I chose the version created by Bing Liu et al3. Each text is compared word by word with this list. A positive word increases the score by one, and a negative word decreases the score by one.

The output is a sentiment score for each tweet in the dataset. It is important to remember that sentiment scores are an approximation. To know someone’s exact opinion, we would have to ask the Twitter user directly. Tweets in which zero words matched the lexicon, and therefore could not be scored, were removed.

Locating tweets

To link sentiment in tweets to vaccination data, a country of origin is required. Every Twitter user can provide their own location when signing up. This makes the location variable quite chaotic. Some users prefer not to provide a location at all, while others list nonsensical places such as “the moon” or “my basement”. Another issue is the use of different names for the same location. For example, “Holland” and “The Netherlands” refer to the same country. These locations need to be standardized for further analyses, so I used the OpenStreetMap API4. After removing all tweets without a location, I sent the remaining ones to their servers. Each valid location yields coordinates, which can be converted into raw GEO data containing the country of origin.

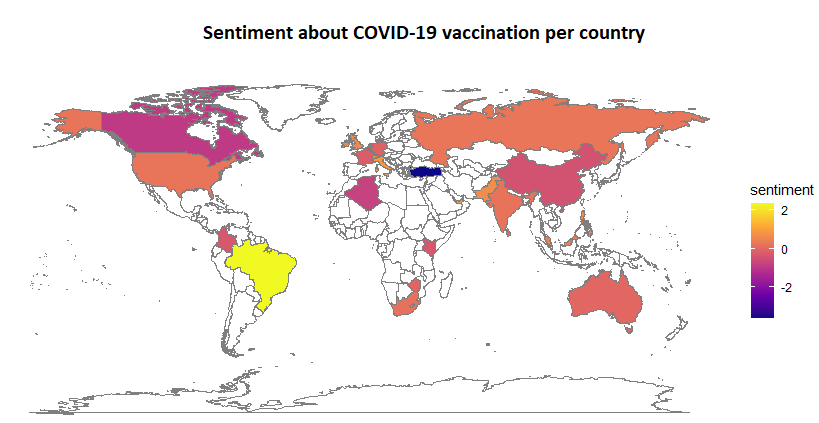

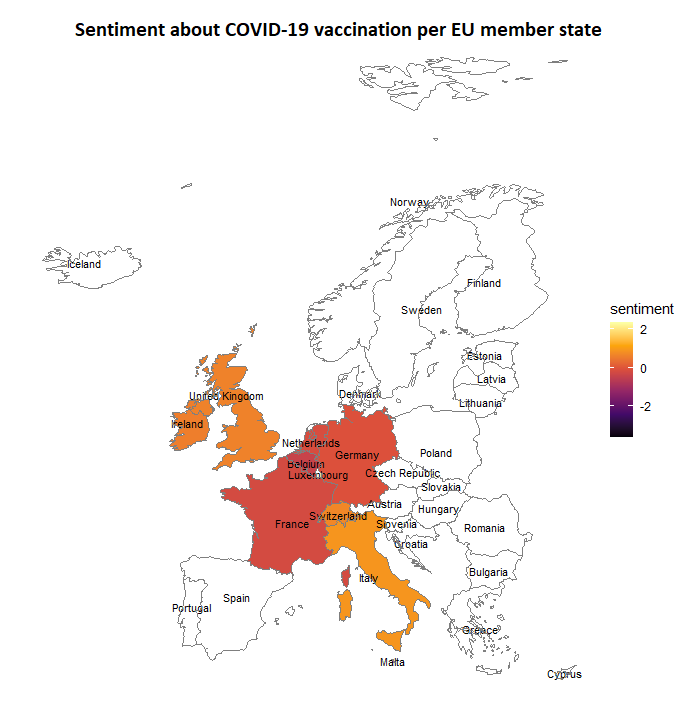

I now have sentiment data over time and per country. With this information, I created maps of the world and of the member states of the European Union, showing the average sentiment about COVID-19 vaccines per country. You will notice that some regions contain no data. These areas had too few tweets to calculate an average sentiment that justifiably represents the entire population. These countries were also excluded from the next analysis.

Brazil has, on average, the most positive views on the vaccine. This is somewhat surprising, since the Brazilian president has been dismissive of vaccinations and the pandemic as a whole5. The country with the most negative opinions is Turkey. This is also surprising, because the Turkish president actively encourages his citizens to get vaccinated6. The efforts, or lack thereof, of an elected government are apparently not automatically reflected in public sentiment. When looking at the European Union, opinions do not differ much and are slightly on the negative side. Similar sentiment is shared across neighbouring countries. The European country with the most positive outlook on vaccines is Italy, which is not entirely surprising since it was hit early and hard by the pandemic in Europe.

Before continuing to the next step, I combined the two datasets into a single one. Each date per country now also includes data on the number of vaccines administered and the average sentiment for that specific country. This makes comparison between variables easier.

Linear Regression

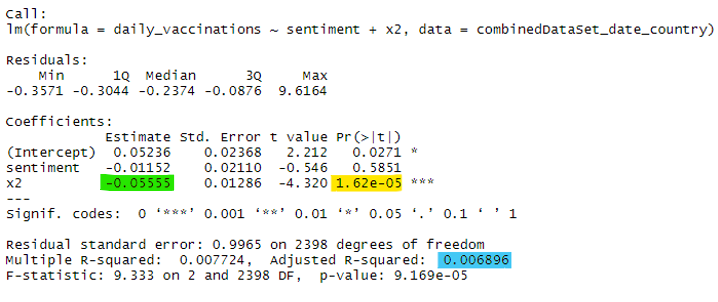

With the final analysis, I can answer the research question. Linear regression compares trends in sentiment with trends in vaccination numbers. The output is a model accompanied by descriptive parameters that indicate how well it performs. Ideally, the model shows a strong effect of sentiment on vaccination numbers and fits the variation present in the data well. Quality is assessed using two parameters. The p-value indicates whether an effect exists and how strong it is. Values of 0.005 or lower are considered significant. The R-squared value explains how much variation in the dataset is covered by the model and also reflects its predictive capabilities. A value of 75 percent or higher would be considered acceptable and accurate. The initial model was of low quality, so optimization was performed, resulting in the following output:

This output is somewhat abstract, so I will explain it using the highlighted values. The p-value is 0.000016, which is well below the margin explained earlier. This means that sentiment does indeed have an effect on the number of vaccines administered, and that effect is statistically strong. However, the model does not explain much of the variation in the data. The R-squared value indicates that only 0.7 percent of the variation is covered by this model. This means that sentiment cannot be used to predict vaccination numbers in the future. Another noteworthy parameter is the estimate. This indicates what happens to sentiment when the vaccination count increases by one. The estimate is slightly negative, meaning that as vaccination numbers increase, overall sentiment declines slightly.

Conclusions

To summarize, sentiment expressed on Twitter has a significant effect on vaccination numbers. I did not fully expect this result. Not everyone gained access to a vaccine at the same time, and vaccine production was occasionally halted. In addition, a significant portion of Twitter accounts consists of bots or trolls attempting to manipulate opinions7. However, sentiment alone is not suitable for predicting future vaccination trends. Other factors, such as age or living conditions, are likely better predictors. Sentiment by itself is insufficient to explain the complex issue of COVID-19 vaccinations. The fact that sentiment decreases as more vaccines are administered says something about our society. The reason for this phenomenon is open to discussion. My personal interpretation is that this trend reflects an increasing divide between supporters and opponents of vaccination. Unvaccinated individuals may feel increased pressure as restrictions are lifted for their vaccinated peers, leading them to express their opinions or frustrations more frequently.

Points for further research

- Compare lexicons and include languages other than English

- Use more data by expanding the set of keywords used to collect tweets

- Compare additional variables besides sentiment

Sources

The R code I made can be found on this GitHub repository

- COVID-19 All Vaccines - Tweets Tweets about all COVID-19 Vaccines, Gabriel Preda

- COVID-19 World Vaccination Progress - Daily and Total Vaccination for COVID-19 in the World from Our World in Data, Gabriel Preda

- Bing Liu and collaborators Lexicon

- OpenStreetMap API Wiki

- Bolsonaro worked to shake Brazil’s faith in vaccines. But even his supporters are racing to get their shots, The Washington Post, 16-08-2021, Terrence McCoy and Gabriela Sá Pessoa

- Turkey's Erdogan receives COVID-19 vaccine, 14-01-2021, Reuters

- Researchers: Nearly Half Of Accounts Tweeting About Coronavirus Are Likely Bots, 20-05-2020, NPR, Bobby Allyn